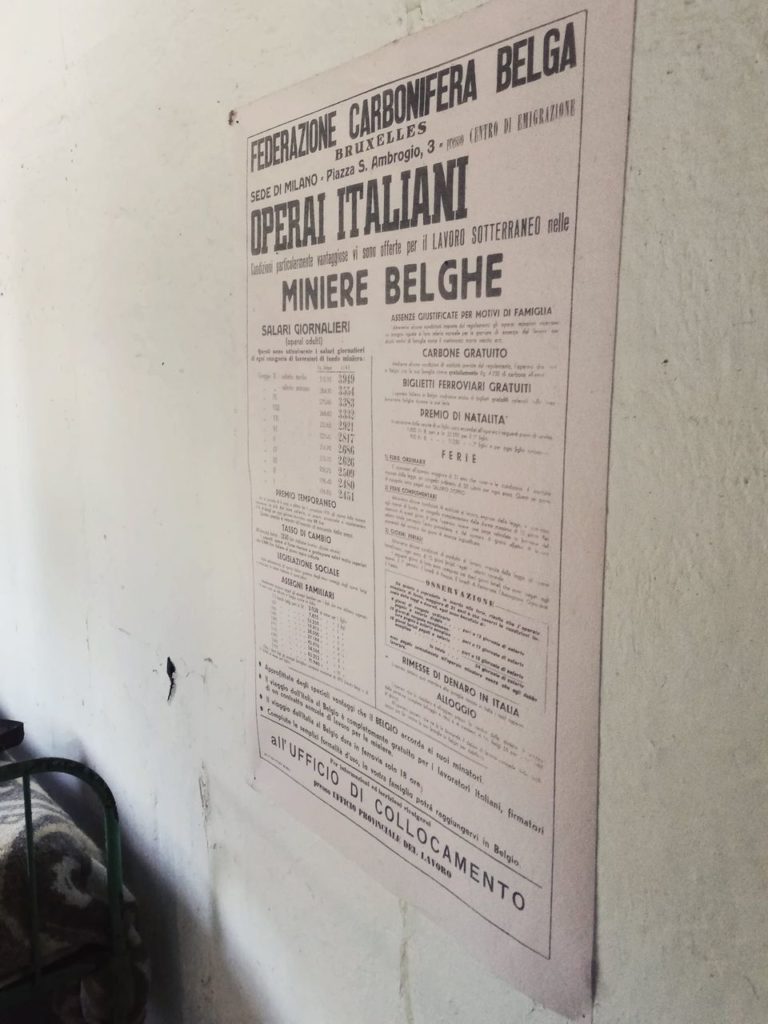

A faded photo on a tombstone in a cemetery in Wallonie. On the left, a plaque bearing a miner lamp. On the right, another plaque with a cross. I fill the missing parts in my uncle’s photo through recollections of the same photo that my mum has kept on a shelf for decades. I have vague memories of my uncle, my mum’s elder brother. 19 years older than her, he left when she was 3. Only that photo, my mum’s stories and my cousins coming over from Belgium from time to time in the summer. My uncle died of silicosis, he was 50. I always wished to go and see where he lived, always postponed. After the Ruskin “crisis” I promised myself never again to allow work to take over my life in the pursuit of a fragile stability. The pandemic reinforced that commitment. So here I am, visiting industrial heritage sites, thinking, with respect and awe, knowing that my uncle with many youngsters of his generation lived in that mining village. An agreement between the Italian and Belgian governments in 1946, brought 50,000 Italian workers in the pits in exchange for coal that would facilitate postwar reconstruction. The miners village is an example of “paternalistic capitalism”, that of course did not care of having workers’ lifespan cut short by an occupational illness or accidents. But my cousins tell me of their childhood, of the sons and daughters of those miners and iron factory workers that left Italy with my uncle, now happily settled with their families, sipping black coffee from a huge moka, in a mix of Venetian, Italian and French that connects of all us. Happy time.